And then there were too many other and more urgent personal matters than Hildegard’s employment of signal tones. My intention to reflect upon my findings when exploring Hildegard’s compositions in the light of the second Gregorian schema was ‘interrupted’. So I summarize my most important findings for the article I will submit soon. These refer to the employment of B in Gregorian chant from both schematic perspectives explained in the previous blogs: that of the first and the second Gregorian schema on the one hand and on the other hand Hildegard’s remarkable approach shown in her Kyrie.

The use of B-durus (‘B’) versus B-molle (‘B-flat’) in Gregorian chant has been a puzzling affair from the traditional analytical perspective of the first Gregorian schema. In Radbod’s compositions we see the B-flat employed as signal tone in a durus environment.

The analysis of B-flat AND B as signal tones often has been obscured by more recent music-reading practices which assume a repetition of an added alteration within the same beat and a repetition of alterations that belong to the key of a composition as notated after the first G/F key sign. In the case of B, confused modal perceptions about inadmissible tritons in medieval Gregorian chant did the rest. The transcription by Pothier of the Kyrie analyzed below is a good example: his transcription shows B-flats everywhere.

So, rule 1. read B-flat only if notated. Rule 2. when interpreting B this way, include the second Gregorian schema in your analysis.

The main characteristic of a signal tone is that it interrupts an expected melodic structure. An expected melodic structure relates to formal aspects. Without interruption no signal.

From a perspective of interruption, the employment of B-flat and B-natural in Hildegard’s compositions becomes less enigmatic. ‘Often’ because the employment of B-flat in Hildegard’s time could be triggered by two considerations:

1. A consideration of the second schema: B-flat as an interruptive signal tone if the environment is defined by B.

2. A consideration of the first (formal melodic) schema resulting in ‘smoothing the melody’ as one contemporaneous comment defines it: avoiding the tritone in an F-B interval.

All analyses I read thus far refer to the smoothing effect of the B-flat in a melodic setting defined by F. But how to compare the occurrences of B-flat in other melodic contexts?

Sergeant’s comparison of Hildegard’s Kyrie contrafact based on the epideictic chant O lucidissima offers food for thought. In the latter chant, Hildegard creates alternatingly B environments and B-flat environments. Both B-versions – natural as well as flat – by their alternative employment reflect signal tones: they interrupt the preceding melodic environment, triggered by the rhetorical relevance of the words accentuated. The analysis in the article demonstrates this hypothesis.

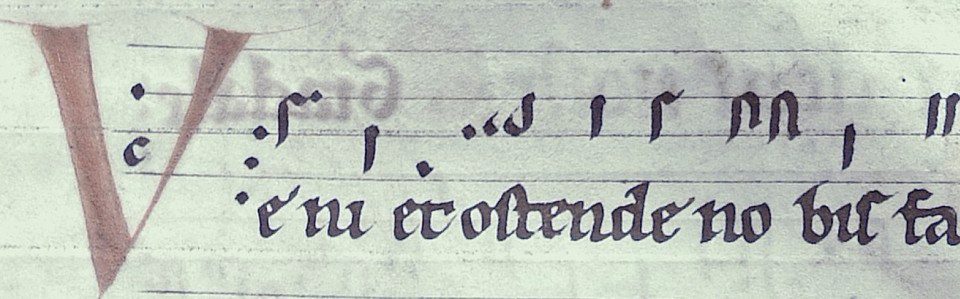

For the Kyrie – purely based on melodic material from O lucidissima – there are no textual triggers that ‘justify’ the interruptive employment of B and B-natural. Looking at the manuscript and reading B-flat only where notated, we see a constant repetition of F-B intervals in the ‘Kyrie leyson’ and ‘Christe leyson’ (sic) pleads, ‘Lord/Christ have mercy’ . These tritonal wails only once are interrupted in the melodic constellation of the second ‘Kyrie leyson’, where Hildegard notates a B-flat. When singing, the emotionally smoothing effect by the contrasting ‘molle’ is remarkable if not baffling.

Here, it is as if Hildegard turns her back to the principia media defining medieval first and second schemas and decides to create melodic tension in a way that reminds of post-modal compositions.

Food for thought indeed.