Home » Articles posted by Leo Lousberg

Auteursarchief: Leo Lousberg

Over intermediale codes in het gregoriaans – een antwoord aan Geert Maessen

Samenvatting

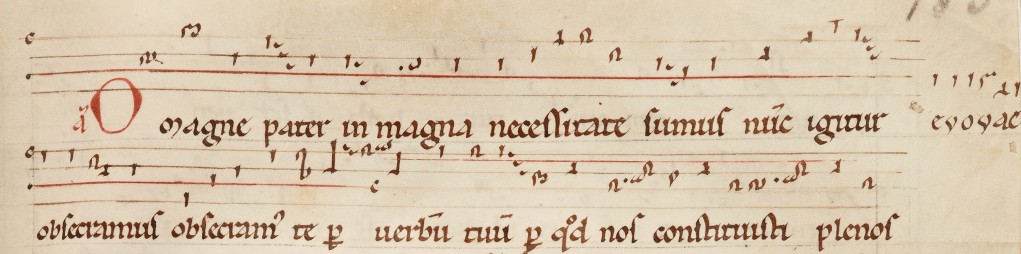

Specifieke klanken en hun symbolen in muzieknotatie werden in het gregoriaans gebruikt als prosodische elementen om te verwijzen naar retorische relevantie in de tekst, zoals het (prosodische accent dat we kennen als) vraagteken met zijn symbool en zijn vaste melodische wending in nagenoeg alle West-Europese talen altijd staat voor de vragende wijs. Alle in mijn artikelen en proefschrift beschreven muziektekens en klanken hebben die prosodische functiekarakteristiek: niet voor de verwijzing naar een vraag maar voor de verwijzing naar retorische relevantie. Signaaltonen zijn intermediale codes: muzikale formules die verwijzen naar de semantische inhoud van de gezongen tekst.

Geert Maessen verwerpt de hypothese dat de speciale tekens in manuscript Montpellier H 159 verwijzen naar retorische relevantie. Het is hem daarbij ontgaan dat de retorische hypothese is gebaseerd op de analyse van een reeks klanktekens (waaronder de speciale tekens in H 159) die tot in de dertiende eeuw retorische relevantie in de tekst benadrukken. Aan de hand van zijn eigen voorbeelden licht ik de retorische hypothese aan de hand van alle signaaltonen (niet alleen microtonen) nogmaals toe.

De door Geert Maessen voorgestelde intonatiehypothese veronderstelt dat de speciale tekens in H 159 aanwijzingen waren om si en mi zuiver (vooral niet te hoog) te intoneren. Hij presenteert zijn bevindingen als kansberekeningen: de kans op een speciaal teken is hoger als bepaalde melodische contexten aanwezig zijn. Daar plaats ik een reeks kanttekeningen bij. Funest voor de intonatiehypothese is dat de speciale tekens vaker zonder dan in combinatie met die contexten worden gebruikt. Onderzoekstechnisch bezien is mijn verwerping van Geert Maessens betoog een herhaling van zetten waarmee Dirk van Betteray in 2007 de retorische verklaring van liquescente neumen verdedigde.

Tot zover deze samenvatting.

De complete tekst kunt u hier downloaden

Perplexed: AI-supported analysis of signal tones

A mail, I sent to some of my friends this morning:

Dear ,

Printed books,

Traveling by rail,

Google,

AI

All labeled as The End of Intellectuality or similar.

You know that I have been experimenting with neume-text retrieval. This morning, I tested some recent ideas. The first results are very promising, if not to say that they might be a major breakthrough for the intermedial analysis of signal tones.

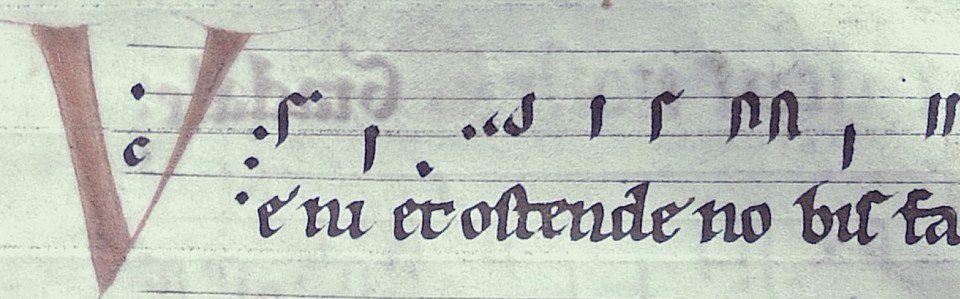

In Perplexity Pro, I uploaded 2 scans:

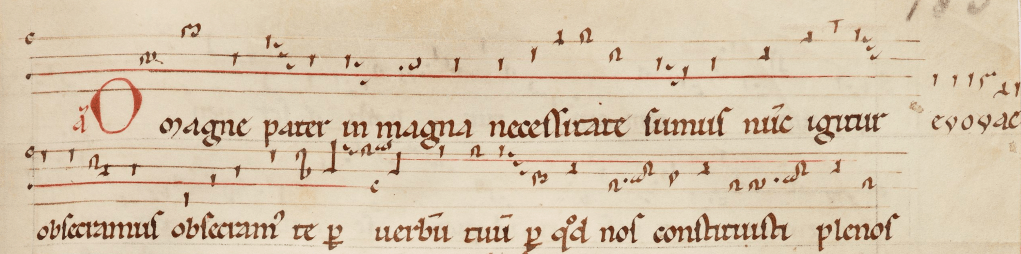

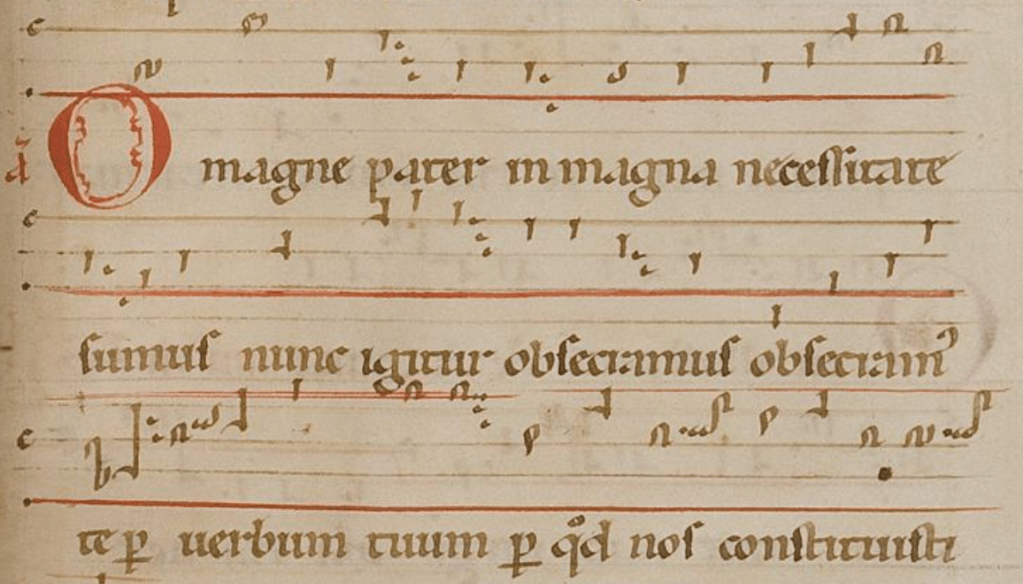

Scan 1: a list with scans of 8 ornamental neumes and their names next to them, copied from U406

Scan 2: a folio from U 406

Command to software: “trace symbol 5, (quilisma) from scan 1 in scan 2 and mention the corresponding complete word to which this symbol applies.”

I could not believe my eyes…. And I even did not ask for their location on the page….

This is only the beginning.

See attachment.

The ms U 406 is problematic because it is bound far too tight. But, for instance, the two main Hildegard sources I am currently analyzing for their signal tones have been scanned with flat pages and their ‘readability’ is 100%.

BiBlo Von Bingen’s Blog 04

And then there were too many other and more urgent personal matters than Hildegard’s employment of signal tones. My intention to reflect upon my findings when exploring Hildegard’s compositions in the light of the second Gregorian schema was ‘interrupted’. So I summarize my most important findings for the article I will submit soon. These refer to the employment of B in Gregorian chant from both schematic perspectives explained in the previous blogs: that of the first and the second Gregorian schema on the one hand and on the other hand Hildegard’s remarkable approach shown in her Kyrie.

The use of B-durus (‘B’) versus B-molle (‘B-flat’) in Gregorian chant has been a puzzling affair from the traditional analytical perspective of the first Gregorian schema. In Radbod’s compositions we see the B-flat employed as signal tone in a durus environment.

The analysis of B-flat AND B as signal tones often has been obscured by more recent music-reading practices which assume a repetition of an added alteration within the same beat and a repetition of alterations that belong to the key of a composition as notated after the first G/F key sign. In the case of B, confused modal perceptions about inadmissible tritons in medieval Gregorian chant did the rest. The transcription by Pothier of the Kyrie analyzed below is a good example: his transcription shows B-flats everywhere.

So, rule 1. read B-flat only if notated. Rule 2. when interpreting B this way, include the second Gregorian schema in your analysis.

The main characteristic of a signal tone is that it interrupts an expected melodic structure. An expected melodic structure relates to formal aspects. Without interruption no signal.

From a perspective of interruption, the employment of B-flat and B-natural in Hildegard’s compositions becomes less enigmatic. ‘Often’ because the employment of B-flat in Hildegard’s time could be triggered by two considerations:

1. A consideration of the second schema: B-flat as an interruptive signal tone if the environment is defined by B.

2. A consideration of the first (formal melodic) schema resulting in ‘smoothing the melody’ as one contemporaneous comment defines it: avoiding the tritone in an F-B interval.

All analyses I read thus far refer to the smoothing effect of the B-flat in a melodic setting defined by F. But how to compare the occurrences of B-flat in other melodic contexts?

Sergeant’s comparison of Hildegard’s Kyrie contrafact based on the epideictic chant O lucidissima offers food for thought. In the latter chant, Hildegard creates alternatingly B environments and B-flat environments. Both B-versions – natural as well as flat – by their alternative employment reflect signal tones: they interrupt the preceding melodic environment, triggered by the rhetorical relevance of the words accentuated. The analysis in the article demonstrates this hypothesis.

For the Kyrie – purely based on melodic material from O lucidissima – there are no textual triggers that ‘justify’ the interruptive employment of B and B-natural. Looking at the manuscript and reading B-flat only where notated, we see a constant repetition of F-B intervals in the ‘Kyrie leyson’ and ‘Christe leyson’ (sic) pleads, ‘Lord/Christ have mercy’ . These tritonal wails only once are interrupted in the melodic constellation of the second ‘Kyrie leyson’, where Hildegard notates a B-flat. When singing, the emotionally smoothing effect by the contrasting ‘molle’ is remarkable if not baffling.

Here, it is as if Hildegard turns her back to the principia media defining medieval first and second schemas and decides to create melodic tension in a way that reminds of post-modal compositions.

Food for thought indeed.

BiBlo – Von Bingen’s Blog 03

Inventio

Inventio in rhetoric is the first step for preparing an oration or a written statement. It consists of drawing up an inventory of essential information to invent arguments. In previous research (starting with my doctoral dissertation in 2018), I gathered information about the employment of signal tones. I developed hypotheses about the schemas that define their interrelations with other musical, textual and rhetorical schemas defining ‘European medieval liturgical chant’. So which information is essential I have found out in the meantime.

Schema theory is a neuropsychological concept that has proven useful describing text-music relations represented by signal tones. For an excellent introduction to what schema theory might imply for the study of this field, see: Ghosh, Vanessa E., and Asaf Gilboa. “What Is a Memory Schema? A Historical Perspective on Current Neuroscience Literature.” Neuropsychologia 53 (2014): 104–14.

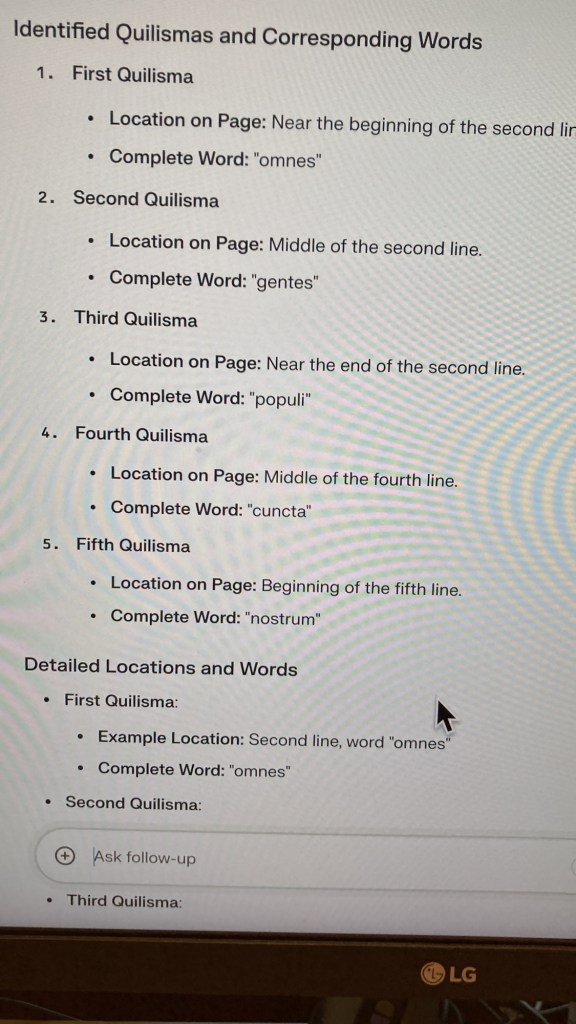

To substantiate my hypotheses about signal tones, I organise information from the internet and from sources in libraries. Basic material often can be found in CANTUS . Fortunately, CANTUS provides indexes for both the Dendermonde manuscript and the Riesencodex. A selection of the fields in the CANTUS indexes for the two manuscripts I imported into Filemaker, database software I have used since 2018 for the inventio of data related to my research. I always set up one layout in which I organize all incoming information, that subsequently is analyzed in other layouts. The ‘General Input’ layout under construction looks like this:

Top left, the metadata of the chant per manuscript provided by CANTUS. Underneath top-down, links to the image of the chant analysed in the digitised sources, the Latin text plus its translation, followed by the centrepiece of the database, a table with words containing signal tones, the signs employed and their rhetorical categorisation. Finally some tables with quantitative summaries about the signal tones registered per chant and in the collection selected (this can be filtered for any subcategories in the database, for instance per genre, per source, etc.).

The right hand part of this layout shows a number of buttons that open other websites I frequently use for gathering the basic stuff for this database and, if relevant, the page or subject links found for quick reference. Below these fields, audio files. I should add information from the discographies available and the chant-specific links but, as said, this is a layout under construction. The Latin text is copied into online text processors, a syllabifier and a hyphenator. The former is used to calculate relative signal tone densities per chant, the latter is the basis for transcription in neoscript by Gregorio software.

The relative signal tone density is calculated by dividing the number of signal tones by the number of syllables per chant; it enables quantitative comparisons of signal tone employments between chants, composers, genres and whatever filter you may think of. Whether it makes sense from a methodological point of view remains to be seen; I do not bother too much because the software does the tedious job for me.

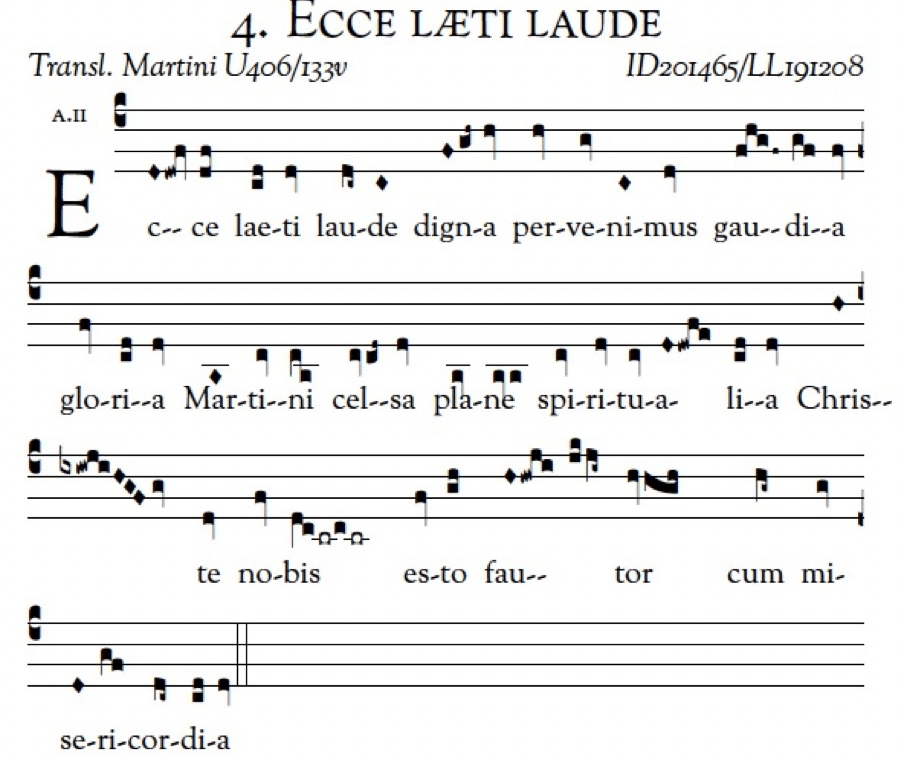

Gregorio software I use to transcribe the chants as notated in the manuscript into material that can be used by choirs. For instance, the following composition by Radbod of Utrecht (899-917), as notated in NL-Uu 406 results in the subsequent notation:

For encoding information about signal tones found in the manuscript, I keep two code tables at hand.

In other layouts in the same Filemaker database for this project, I assemble my notes from secondary literature. Separate layouts will combine the manuscript image with my findings per chant and/or filtered data from the respective manuscripts, comparisons etc.

Which signs in Hildegard’s compositions are signal tones I will sow in the next blog.

BiBlo – Von Bingen’s Blog, 02

The Sources

The chants composed by Hildegard have been notated in two manuscripts. The notation is a representative of what the Utrecht musicologist Ike de Loos in 1997 described as the Utrecht-Stavelot-Trier notation, after her analysis of sources written in this geographic triangle. The neumes are variants of the so-called Messine notation, the neumes that are characteristic for the tradition developed in Metz, France.

The Utrecht-Stavelot-Trier Triangle. Rupertsberg in red.

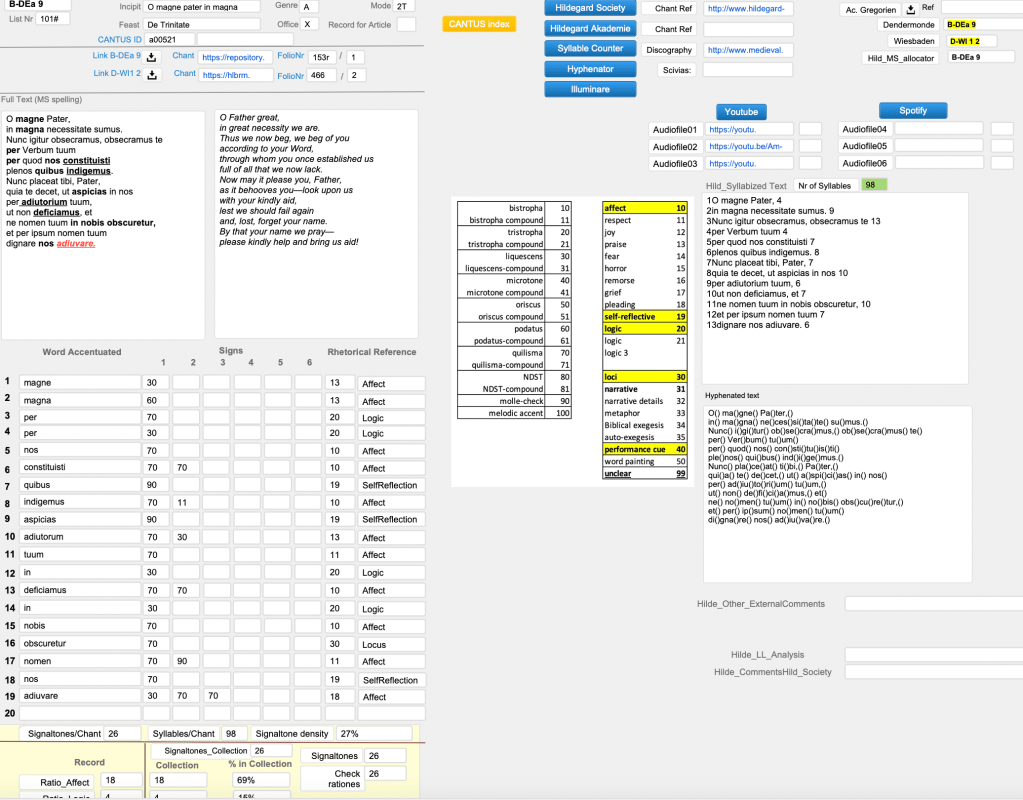

The Utrecht-Stavelot-Trier notation:

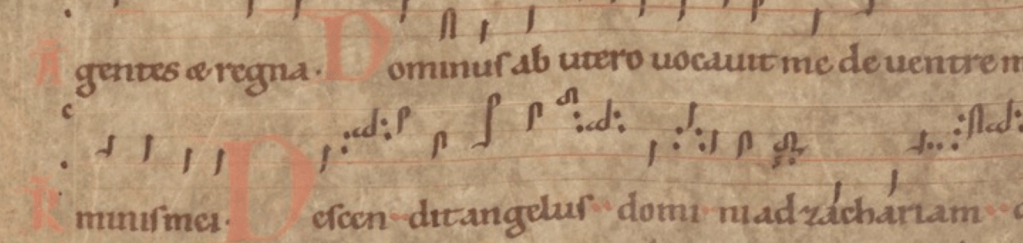

Utrecht, NL-Uu 406/ 125v

The notation of Hildegard’s compositions:

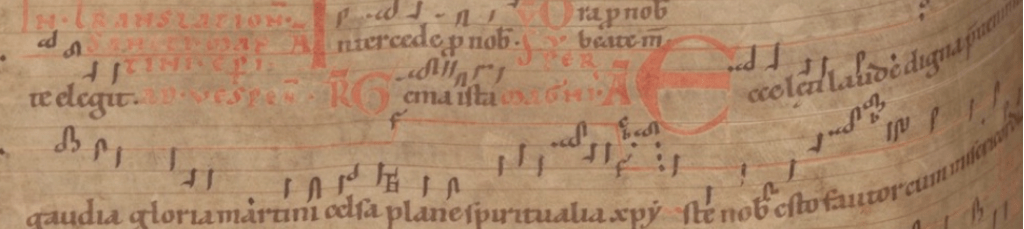

- Dendermonde B-DE a 9/f. 153r/1

2. Riesenkodex D- WI1 2 /466r/4

Both manuscripts were produced at Rupertsberg Abbey. Dendermonde was dictated by Hildegard to her scribe Guibert of Gembloux a few years before she died; it was sent to an abbey in what now is known as Belgium and ended up in the Benedictine Abbey of Dendermonde, Flanders. Since 2017, the Alamire Foundation in Leuven, Belgium, keeps this manuscript.

The same scribe reorganised the Dendermonde version a few years after her death, in what became known as the Riesencodex, now kept at Hessische Landesbibliothek, Wiesbaden. There is some debate whether Hildegard or Guibert composed the chants.

For my analysis, I intend to select a number of chants notated in both manuscripts for comparing the employment of signal tones. Which ones will depend upon the first steps of my research into the employment of signal tones in the compositions attributed to Hildegard.

The presentation of my research’s setup is a nice step towards an introduction to rhetoric, which is the essence connecting language and music in plainchant. An orator started by gathering information and arguments that might support his explanation. This first step of the rhetorical preparation is called Inventio: drawing up an inventory and inventing arguments.

BiBlo – Von Bingen’s Blog, 01

This blog offers new perspectives on the compositions by Hildegard von Bingen. It is meant for singers and researchers.

Now, “new perspectives”: isn’t that quite presumptuous, given the avalanche of publications and recordings that pour from the screen after you put her name in a search machine?

• Yes, if you know what signal tones are;

• No, if you haven’t the faintest clue what signal tones might be.

That is what this blog is about, more specifically about the signal tones in the Symphonia composed by Hildegard von Bingen (1098-1179), at her abbey near Rüdesheim am Rhein, half an hour by car from where I had my office for almost 14 years: Wiesbaden.

What do signal tones add to our knowledge about Hildegard and her time?

Up to about the middle of the thirteenth century, liturgical melodies were notated by neumes, since the eleventh century by neumes on a staff. By that time, they could represent pitches of all sorts, dynamic accentuations, and timbral aspects. Since about the turn of the second millennium, musicologists have discovered that certain neumes (and the sounds they might represent) also are melodic codes, conveying messages about text content.

To the list of signal tones discovered in separate studies, I added microtones in 2018, synthesising previous research and my own into a new tool for analysing text by these signal tones (that I called ‘musemes’ in my doctoral thesis, but in normal language, ‘signal tones’ make more sense). All ten signs for signal tones (and the corresponding sounds) mean just one thing: “the text has rhetorical relevance”, just like the question mark means one thing: “this is an interrogative expression”. Imagine ten different signs for the question mark and you understand the concept of the signal tone. Which of the signal tones was applicable depended upon text/melody situations to which I will come back in other blogs.

Signal tones were employed all over Europe up to about 1250. Combinations of more than one symbol in one word simply meant that it was more important. If you learn the ten musical signs representing signal tones, you catch about 95% of the encoded medieval communication hidden in musical notation. No need for a BA or MA Musicology, no need to understand the signs that represent other (more standard) melodic issues.

Just ten music symbols, separate and in combination, reveal that Hildegard implanted a textual waypoint in her melody. That is the easy part; as a musicologist, I may be of some help by the blogs that I intend to publish during the next months.

Interpreting why she added them sometimes is more difficult.

Dan Brown, Templars? Kind of.

Do not expect signal tones helping you cracking the secret to eternal youth, but exciting it is for sure: signal tones are echoes of medieval minds. Learning to communicate in the Middle Ages meant studying RRR: Reading, wRiting, and Rhetoric, and it is impossible to overstate the importance of the latter. All literate people were aware that all oral, written, and symbolic communication via the arts was conveyed on a rhetorical grid. If an orator, singer, writer accentuated a word, an expression or a sentence, both sending and receiving this information was guided by rhetorical education.

In plainchant, signal tones were the sung rhetorical messengers.

Thousands of notated manuscripts still exist, written from Malta to Reykjavik and by the month, more are available for consultation for free. Have a look at the Database CANTUS and the MMMO database, to which I contributed also. The Symphonia are notated in two manuscripts, one from a Belgian Benedictine abbey in Dendermonde kept at the Alamire Library in Leuven, the other is the so-called Riesenkodex from Wiesbaden. We will have a look at them in the next blog.

Before summer, I intend to send my ‘Hildegard-signal tones’ exploration to a musicological journal; readers will be able to follow my research (not my drafts).

Comments are welcome!

Voor de Poorten van een Gelukkige Stad!

Het is zondagmiddag 3 juli. Vanavond opent om 19:00 uur opent Gregoriaans Koor Utrecht met dirigent Anthony Zielhorst de festiviteiten die het resultaat zijn van een samenwerking van het koor met Prof. dr. Els Rose, Universiteit Utrecht en onze Gregorius Fundatie die al startte in 2020: Het Wonder van Sint-Maarten: de Gelukkige Stad! het project maakt deel uit van de feestelijkheden rond Utrecht 900 jaar stadsrecht.

De integrale uitvoering van alle 42 gezangen van het officie Translatio Martini zoals genoteerd in U406 – een Utrechts handschrift uit de twaalfde eeuw – en getranscribeerd door de Gregorius Fundatie in het kader van dit project maakt deel uit van dit project. Vanavond worden de eerste vespers (19:00-19:45) en de metten gezongen. (21:00-23:00 uur).

Een documentaire van RTVU die voor het eerst werd uitgezonden op 12 juni 2022 vat het project uitstekend samen.

In de documentaire van filmmaker Daniël Brüggen is countertenor Oscar Verhaar te zien en te horen tijdens een repetitie voor een uitvoering tijdens Festival Oude Muziek Utrecht op 2 september 2021. Graag had ik de registratie van mijn lezing tijdens het Festival Oude Muziek Utrecht op 2 september 2021 hier laten zien met prachtige opnamen van Oscar als solist ondersteund door het koor. Maar de organisatie geeft de rechten niet vrij.

Daarom een audio-opname van de generale repetitie van Cadent a latere; dat is een deel van de tractus Qui habitat die in de Middeleeuwen altijd op Goede Vrijdag werd gezongen.

Koude rillingen, iedere keer als ik dit hoor. Prachtig.

Binnenkort is een complete videoregistratie van het officie beschikbaar op de website van Het Utrechts Archief.

De tractus Qui habitat met signaaltonen: “Beter dan de Matthäus Passion”

Op 2 september gaf countertenor Oscar Verhaar en Gregoriaans Koor Utrecht onder leiding van Anthony Zielhorst een concert. Leo Lousberg gaf een toelichting.

Het concert werd gegeven in de Janskerk in het kader van het Festival Oude Muziek Utrecht 2021.

Het was een initiatief van de Gregorius Fundatie, dat financieel tevens werd gesteund door:

• Fentener van Vlissingen Fonds

• Carel Nengerman Fonds

• K.F. Hein Fonds

• Elize Mathilde Fonds

• De Van Baaren Stichting en

• Stichting Organisatie Oude Muziek

Er waren rond 90 bezoekers, en daarmee was de kerk volgens de geldende COVID-regels vol. Via eMTV is het concert met de lezing voor het luttele bedrag van € 2,50 nog te zien tot 17 oktober 2021: hier de link.

Het koor voerde een aantal gezangen uit van bisschop Radboud van Utrecht, door hem gecomponeerd rond 910 ter ere van de stadspatroon Sint-Maarten. Oscar Verhaar zong acht verzen van de tractus Qui habitat, waarvan het laatste begeleid door isontonen, gezongen door het koor. Het klankbeeld verplaatste de aanwezigen in een sfeer die de middeleeuwse beleving van de passieweek wellicht benaderde.

Hoewel signaaltonen in principe geen woordschilderingen zijn en een breder retorisch bereik hebben dan alleen emotie, werd dat laatste aspect door de context van de uitvoering wel benadrukt.

“Dit is beter dan de Mattäus Passion” zei me een enthousiaste toehoorder.

Inderdaad: koude rillingen, zo mooi.

Hoge en heldere stemmen

Op donderdag 2 september om 09:30 uur in de Janskerk te Utrecht zingt countertenor Oscar Verhaar de tractus Qui habitat met microtonen en andere middeleeuwse signaaltonen. Ik geef donderdag uitleg over de recentelijk herontdekte gregoriaanse signaaltonen. Countertenors werden in Karolingische tijden voor liturgische gezangen gewaardeerd. Waren die hoge stemmen dan geen jongensstemmen maar countertenors?

Ja, is het antwoord. In een 12-e eeuwse ontkenning ligt de bevestiging opgesloten: “die feminiene stemmen moeten niet klinken in de kerk…..en zangers die zo zingen mogen niet tot voorzanger worden bevorderd.”

Ik verheug me op zijn optreden, samen met Gregoriaans Koor Utrecht olv Anthony Zielhorst.

ID-bewijs en QR-code nodig voor toegang!!

Goede Vrijdag, A.D. 1051

In de Janskerk werden dezelfde verzen van de tractus Qui habitat gezongen als overmorgen, 970 jaar later.

We zingen die verzen uit een Utrechts missaal, geschreven rond 1200. Daarin staan de codes van de literati nog steeds tussen de symbolen van de gregoriaanse muzieknotatie. Symbolen voor klanken waarmee zangers tijdens liturgische vieringen de gezongen teksten annoteerden. Oscar Verhaar en Gregoriaans Koor Utrecht olv Anthony Zielhorst.

Donderdag 2 september, 09:30 Janskerk Utrecht #Festival Oude Muziek